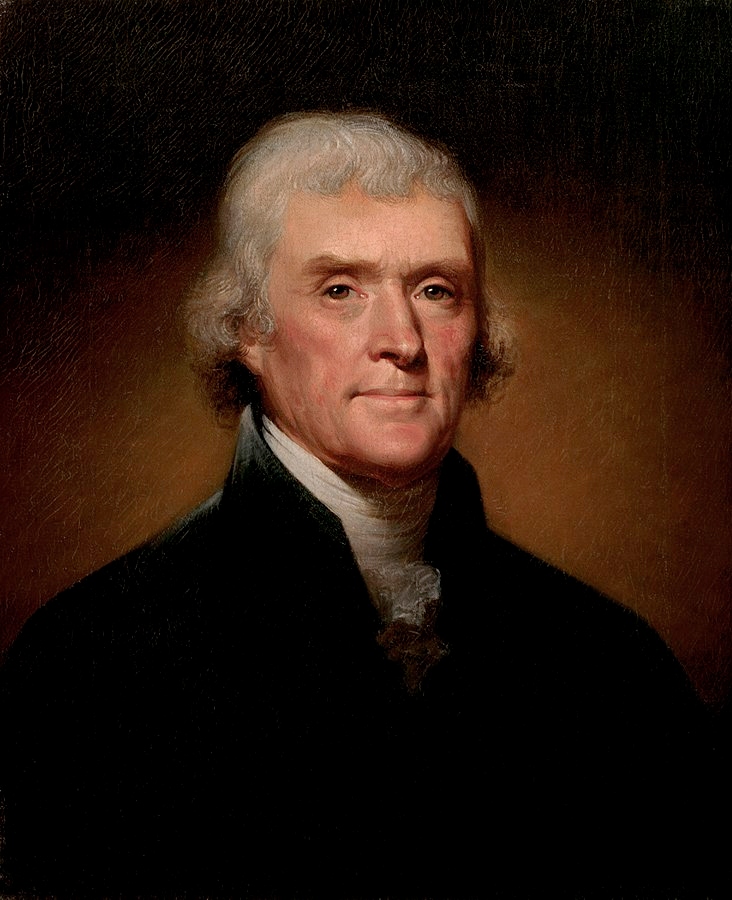

Thomas Jefferson was a Founding Father of the United States who wrote the Declaration of Independence. As U.S. president, he completed the Louisiana Purchase.

Thomas Jefferson was the primary draftsman of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, the nation’s first secretary of state and the second vice president (under John Adams). As the third president of the United States, Jefferson stabilized the U.S. economy and defeated pirates from North Africa during the Barbary War. He was responsible for doubling the size of the United States by successfully brokering the Louisiana Purchase. He also founded the University of Virginia.

Early Life

Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, at the Shadwell plantation located just outside of Charlottesville, Virginia.

Jefferson was born into one of the most prominent families of Virginia’s planter elite. His mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson, was a member of the proud Randolph clan, a family claiming descent from English and Scottish royalty.

His father, Peter Jefferson, was a successful farmer as well as a skilled surveyor and cartographer who produced the first accurate map of the Province of Virginia. The young Jefferson was the third born of 10 siblings.

As a boy, Jefferson’s favorite pastimes were playing in the woods, practicing the violin and reading. He began his formal education at the age of nine, studying Latin and Greek at a local private school run by the Reverend William Douglas.

In 1757, at the age of 14, he took up further study of the classical languages as well as literature and mathematics with the Reverend James Maury, whom Jefferson later described as “a correct classical scholar.”

College of William and Mary

In 1760, having learned all he could from Maury, Jefferson left home to attend the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia’s capital.

Although it was the second oldest college in America (after Harvard), William and Mary was not at that time an especially rigorous academic institution. Jefferson was dismayed to discover that his classmates expended their energies betting on horse races, playing cards and courting women rather than studying.

Nevertheless, the serious and precocious Jefferson fell in with a circle of older scholars that included Professor William Small, Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier and lawyer George Wythe, and it was from them that he received his true education.

Becoming a Lawyer

After three years at William and Mary, Jefferson decided to read law under Wythe, one of the preeminent lawyers of the American colonies. There were no law schools at this time; instead aspiring attorneys “read law” under the supervision of an established lawyer before being examined by the bar.

Wythe guided Jefferson through an extraordinarily rigorous five-year course of study (more than double the typical duration); by the time Jefferson won admission to the Virginia bar in 1767, he was already one of the most learned lawyers in America.

Monticello

In 1770, Jefferson began construction of what was perhaps his greatest labor of love: Monticello, his house atop a small rise in the Piedmont region of Virginia. The house was built on land his father had owned since 1735.

In keeping with the interests of one of America’s greatest “Renaissance Men” — Jefferson’s interests ranged from botany and archaeology to music and birdwatching — Jefferson himself drafted the blueprints for Monticello’s neoclassical mansion, outbuildings and gardens.

More than just a residence, Monticello was also a working plantation, where Jefferson kept roughly 130 African Americans in slavery. Their duties included tending gardens and livestock, plowing fields and working at the on-site textile factory.

Thomas Jefferson’s Children

From 1767 to 1774, Jefferson practiced law in Virginia with great success, trying many cases and winning most of them. During these years, he also met and fell in love with Martha Wayles Skelton, a recent widow and one of the wealthiest women in Virginia.

The pair married on January 1, 1772. Thomas and Martha Jefferson had six children together, but only two survived into adulthood: Martha, their firstborn, and Mary, their fourth. Only Martha survived her father.

His six children with Martha, however, were not the only children Jefferson fathered.

Sally Hemings

History scholars and a significant body of DNA evidence indicate that Jefferson had an affair – and at least one child – with one of his slaves, a woman named Sally Hemings, who was in fact Martha Jefferson’s half-sister.

Sally’s mother, Betty Hemings, was a slave owned by Jefferson’s father-in-law, John Wayles, who was the father of Betty’s daughter Sally. It is overwhelmingly likely, if not absolutely certain, that Jefferson fathered all six of Sally Hemings’ children.

Most compelling is DNA evidence showing that some male member of the Jefferson family fathered Hemings’ children, and that it was not Samuel or Peter Carr, the only two of Jefferson’s male relatives in the vicinity at the relevant times.

Political Career

The beginning of Jefferson’s professional life coincided with great changes in Great Britain’s 13 colonies in America.

The conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763 left Great Britain in dire financial straits; to raise revenue, the Crown levied a host of new taxes on its American colonies. In particular, the Stamp Act of 1765, imposing a tax on printed and paper goods, outraged the colonists, giving rise to the American revolutionary slogan, “No taxation without representation.”

Eight years later, on December 16, 1773, colonists protesting a British tea tax dumped 342 chests of tea into the Boston Harbor in what is known as the Boston Tea Party. In April 1775, American militiamen clashed with British soldiers at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the first battles in what developed into the Revolutionary War.

Jefferson was one of the earliest and most fervent supporters of the cause of American independence from Great Britain. He was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1768 and joined its radical bloc, led by Patrick Henry and George Washington.

In 1774, Jefferson penned his first major political work, A Summary View of the Rights of British America, which established his reputation as one of the most eloquent advocates of the American cause.

A year later, in 1775, Jefferson attended the Second Continental Congress, which created the Continental Army and appointed Jefferson’s fellow Virginian, George Washington, as its commander-in-chief. However, the Congress’ most significant work fell to Jefferson himself.

Declaration of Independence

In June 1776, the Congress appointed a five-man committee (Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston) to draft a Declaration of Independence.

The committee then chose Jefferson to author the declaration’s first draft, selecting him for what Adams called his “happy talent for composition and singular felicity of expression.” Over the next 17 days, Jefferson drafted one of the most beautiful and powerful testaments to liberty and equality in world history.

The document opened with a preamble stating the natural rights of all human beings and then continued on to enumerate specific grievances against King George III that absolved the American colonies of any allegiance to the British Crown.

Although the version of the Declaration of Independence adopted on July 4, 1776, had undergone a series of revisions from Jefferson’s original draft, its immortal words remain essentially his own: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights; that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

After authoring the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson returned to Virginia, where, from 1776 to 1779, he served as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. There he sought to revise Virginia’s laws to fit the American ideals he had outlined in the Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson successfully abolished the doctrine of entail, which dictated that only a property owner’s heirs could inherit his land, and the doctrine of primogeniture, which required that in the absence of a will a property owner’s oldest son inherited his entire estate.

Separation of Church and State

In 1777, Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which established freedom of religion and the separation of church and state.

Although the document was not adopted as Virginia state law for another nine years, it was one of Jefferson’s proudest life accomplishments.

Governor of Virginia

On June 1, 1779, the Virginia legislature elected Jefferson as the state’s second governor. His two years as governor proved the low point of Jefferson’s political career. Torn between the Continental Army’s desperate pleas for more men and supplies and Virginians’ strong desire to keep such resources for their own defense, Jefferson waffled and pleased no one.

As the Revolutionary War progressed into the South, Jefferson moved the capital from Williamsburg to Richmond, only to be forced to evacuate that city when it, rather than Williamsburg, turned out to be the target of British attack.

On June 1, 1781, the day before the end of his second term as governor, Jefferson was forced to flee his home at Monticello (located near Charlottesville, Virginia), only narrowly escaping capture by the British cavalry. Although he had no choice but to flee, his political enemies later pointed to this inglorious incident as evidence of cowardice.

Jefferson declined to seek a third term as governor and stepped down on June 4, 1781. Claiming that he was giving up public life for good, he returned to Monticello, where he intended to live out the rest of his days as a gentleman farmer surrounded by the domestic pleasures of his family, his farm and his books.

Notes on the State of Virginia

To fill his time at home, in late 1781, Jefferson began working on his only full-length book, the modestly titled Notes on the State of Virginia.

While the book’s ostensible purpose was to outline the history, culture and geography of Virginia, it also provides a window into Jefferson’s political philosophy and worldview.

Contained in Notes on the State of Virginia is Jefferson’s vision of the good society he hoped America would become: a virtuous agricultural republic, based on the values of liberty, honesty and simplicity and centered on the self-sufficient yeoman farmer.

Thomas Jefferson’s Slaves

Jefferson’s writings also shed light on his contradictory, controversial and much-debated views on race and slavery. Jefferson owned slaves through his entire life, and his very existence as a gentleman farmer depended on the institution of slavery.

Like most white Americans of that time, Jefferson held views we would now describe as nakedly racist: He believed that blacks were innately inferior to whites in terms of both mental and physical capacity.

Nevertheless, he claimed to abhor slavery as a violation of the natural rights of man. He saw the eventual solution of America’s race problem as the abolition of slavery followed by the exile of former slaves to either Africa or Haiti, because, he believed, former slaves could not live peacefully alongside their former masters.

As Jefferson wrote, “We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

Minister to France

Jefferson was spurred back into public life by private tragedy: the untimely death of his beloved wife, Martha, on September 6, 1782, at the age of 34.

After months of mourning, in June 1783, Jefferson returned to Philadelphia to lead the Virginia delegation to the Confederation Congress. In 1785, that body appointed Jefferson to replace Benjamin Franklin as U.S. minister to France.

Although Jefferson appreciated much about European culture — its arts, architecture, literature, food and wines — he found the juxtaposition of the aristocracy’s grandeur and the masses’ poverty repellant. “I find the general fate of humanity here, most deplorable,” he wrote in one letter.

In Europe, Jefferson rekindled his friendship with John Adams, who served as minister to Great Britain, and Adams’ wife, Abigail Adams. The educated and erudite Abigail, with whom Jefferson maintained a lengthy correspondence on a wide variety of subjects, was perhaps the only woman he ever treated as an intellectual equal.

Jefferson’s official duties as minister consisted primarily of negotiating loans and trade agreements with private citizens and government officials in Paris and Amsterdam.

After nearly five years in Paris, Jefferson returned to America at the end of 1789 with a much greater appreciation for his home country. As he wrote to his good friend, James Monroe, “My God! How little do my countrymen know what precious blessings they are in possession of, and which no other people on earth enjoy.”

Secretary of State

Jefferson arrived in Virginia in November 1789 to find George Washington waiting for him with news that Washington had been elected the first president of the United States of America, and that he was appointing Jefferson as his secretary of state.

Besides Jefferson, Washington’s most trusted advisor was Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. A dozen years younger than Jefferson, Hamilton was a New Yorker and war hero who, unlike Jefferson and Washington, had risen from humble beginnings.

Jefferson’s Political Party

Rancorous partisan battles emerged to divide the new American government during Washington’s presidency.

On one side, the Federalists, led by Hamilton, advocated for a strong national government, broad interpretation of the U.S. Constitution and neutrality in European affairs.

On the other side, the Republican political party, led by Jefferson, promoted the supremacy of state governments, a strict constructionist interpretation of the Constitution and support for the French Revolution.

Washington’s two most trusted advisors thus provided nearly opposite advice on the most pressing issues of the day: the creation of a national bank, the appointment of federal judges and the official posture toward France.

On January 5, 1794, frustrated by the endless conflicts, Jefferson resigned as secretary of state, once again abandoning politics in favor of his family and farm at his beloved Monticello.

Jefferson as Vice President

In 1797, despite Jefferson’s public ambivalence and previous claims that he was through with politics, the Republicans selected Jefferson as their candidate to succeed George Washington as president.

In those days, candidates did not campaign for office openly, so Jefferson did little more than remain at home on the way to finishing a close second to then-Vice President John Adams in the electoral college, which, by the rules of the time, made Jefferson the new vice president.

Besides presiding over the U.S. Senate, the vice president had essentially no substantive role in government. The long friendship between Adams and Jefferson had cooled due to political differences (Adams was a Federalist), and Adams did not consult his vice president on any important decisions.

To occupy his time during his four years as vice president, Jefferson authored A Manual of Parliamentary Practice, one of the most useful guides to legislative proceedings ever written, and served as the president of the American Philosophical Society.

Presidency

John Adams’ presidency revealed deep fissures in the Federalist Party between moderates such as Adams and Washington and more extreme Federalists like Alexander Hamilton.

In the presidential election of 1800, the Federalists refused to back Adams, clearing the way for the Republican candidates Jefferson and Aaron Burr to tie for first place with 73 electoral votes each. After a long and contentious debate, the House of Representatives selected Jefferson to serve as the third U.S. president, with Burr as his vice president.

The election of Jefferson in 1800 was a landmark of world history, the first peacetime transfer of power from one party to another in a modern republic.

Delivering his inaugural address on March 4, 1801, Jefferson spoke to the fundamental commonalities uniting all Americans despite their partisan differences. “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle,” he stated. “We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

Accomplishments

President Jefferson’s accomplishments during his first term in office were numerous, remarkably successful and productive.

In keeping with his Republican values, Jefferson stripped the presidency of all the trappings of European royalty, reduced the size of the armed forces and government bureaucracy and lowered the national debt from $80 million to $57 million in his first two years in office.

Nevertheless, Jefferson’s most important achievements as president all involved bold assertions of national government power and surprisingly liberal readings of the U.S. Constitution.

Louisiana Purchase

Jefferson’s most significant accomplishment as president was the Louisiana Purchase. In 1803, he acquired land stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains from cash-strapped Napoleonic France for the bargain price of $15 million, thereby doubling the size of the nation in a single stroke.

He then devised the wonderfully informative Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore, map out and report back on the new American territories.

Tripoli Pirates

Jefferson also put an end to the centuries-old problem of Tripoli pirates from North Africa disrupting American shipping in the Mediterranean. During the Barbary War, Jefferson forced the pirates to capitulate by deploying new American warships.

Notably, both the Louisiana Purchase and the undeclared war against the Barbary pirates conflicted with Jefferson’s much-avowed Republican values. Both actions represented unprecedented expansions of national government power, and neither was explicitly sanctioned by the Constitution.

Second Term as President

Although Jefferson easily won re-election in 1804, his second term in office proved much more difficult and less productive than his first. He largely failed in his efforts to impeach the many Federalist judges swept into government by the Judiciary Act of 1801.

However, the greatest challenges of Jefferson’s second term were posed by the war between Napoleonic France and Great Britain. Both Britain and France attempted to prevent American commerce with the other power by harassing American shipping, and Britain in particular sought to impress American sailors into the British Navy.

In response, Jefferson passed the Embargo Act of 1807, suspending all trade with Europe. The move wrecked the American economy as exports crashed from $108 million to $22 million by the time he left office in 1809. The embargo also led to the War of 1812 with Great Britain after Jefferson left office.

Post Presidency

On March 4, 1809, after watching the inauguration of his close friend and successor James Madison, Jefferson returned to Virginia to live out the rest of his days as “The Sage of Monticello.”

Jefferson’s primary pastime was endlessly rebuilding, remodeling and improving his home and estate, at considerable expense.

A Frenchman, Marquis de Chastellux, quipped, “it may be said that Mr. Jefferson is the first American who has consulted the Fine Arts to know how he should shelter himself from the weather.”

University of Virginia

Jefferson also dedicated his later years to organizing the University of Virginia, the nation’s first secular university. He personally designed the campus, envisioned as an “academical village,” and hand-selected renowned European scholars to serve as its professors.

The University of Virginia opened its doors on March 7, 1825, one of the proudest days of Jefferson’s life.

Jefferson also kept up an outpouring of correspondence at the end of his life. In particular, he rekindled a lively correspondence on politics, philosophy and literature with John Adams that stands out among the most extraordinary exchanges of letters in history.

Nevertheless, Jefferson’s retirement was marred by financial woes. To pay off the substantial debts he incurred over decades of living beyond his means, Jefferson resorted to selling his cherished personal library to the national government to serve as the foundation of the Library of Congress.

Death

Jefferson died on July 4, 1826 — the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence — only a few hours before John Adams passed away in Massachusetts.

In the moments before he passed, Adams spoke his last words, eternally true if not in the literal sense in which he meant them, “Thomas Jefferson survives.”

Legacy

As the author of the Declaration of Independence, the foundational text of American democracy and one of the most important documents in world history, Jefferson will be forever revered as one of the great American Founding Fathers. However, Jefferson was also a man of many contradictions.

Jefferson was the spokesman of liberty and a racist slave owner, a champion of the common people and a man with luxurious and aristocratic tastes, a believer in limited government and a president who expanded governmental authority beyond the wildest visions of his predecessors, a quiet man who abhorred politics and arguably the most dominant political figure of his generation.

The tensions between Jefferson’s principles and practices make him all the more apt a symbol for the nation he helped create, a nation whose shining ideals have always been complicated by a complex history.

Jefferson is buried in the family cemetery at his beloved Monticello, in a grave marked by a plain gray tombstone. The brief inscription it bears, written by Jefferson himself, is as noteworthy for what it excludes as what it includes.

The inscription suggests Jefferson’s humility as well as his belief that his greatest gifts to posterity came in the realm of ideas rather than the realm of politics: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and father of the University Of Virginia.”

• Thomas Jefferson was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. Previously, he had served as the second vice president of the United States from 1797 to 1801.

• Born: April 13, 1743, Shadwell, VA

• Died: July 4, 1826, Monticello, VA

• Presidential term: March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809

• Spouse: Martha Jefferson (m. 1772–1782)

• Children: Martha Jefferson Randolph, Madison Hemings

• Vice presidents: Aaron Burr (1801–1805), George Clinton (1805–1809)

• First president to be inaugurated in Washington, D.C.

• First president inaugurated in the 19th century.

• First president whose inauguration was not attended by his immediate predecessor.

• First president to live a full presidential term in the White House.

• First president elected as a Democratic-Republican.

• First president to have previously been a governor.

• First president to have been ambassador to France.

• First president to have previously served as secretary of state.

• First president to defeat the man (Adams) whom he had previously lost to in a presidential election.

• First president to have been widowed prior to his inauguration.

• First president whose election was decided in the House of Representatives.

• First president to cite the doctrine of executive privilege.

• First president to have a vice president elected under the 12th Amendment. Originally the runner-up in the presidential election was named vice president.

• First president to have two vice presidents.

• First president whose vice president was older than him.

• First president to be a deist.

• First president to win election after having been previously defeated.

• First president who died on Independence Day (Along with his predecessor John Adams).

• First president to be survived by his predecessor as president.

• First president to serve as rector of the University of Virginia.